Washington Projects

Revisiting and gathering the grey literature – inclusion of historic documents, genealogy, and other overlooked resource materials.

Washington state, local governments and federal agencies various environmental regulations often require the need for private developers to comply with that include an architectural, archaeological, or cultural resource survey to determine if there is a potential to have an adverse effects on protected properties and archaeological sites. Abbott Cultural Heritage often partners with other environmental consultants to assist in this process, and here are a few recent projects where the grey literature shed light on the cultural landscape and what shaped it.

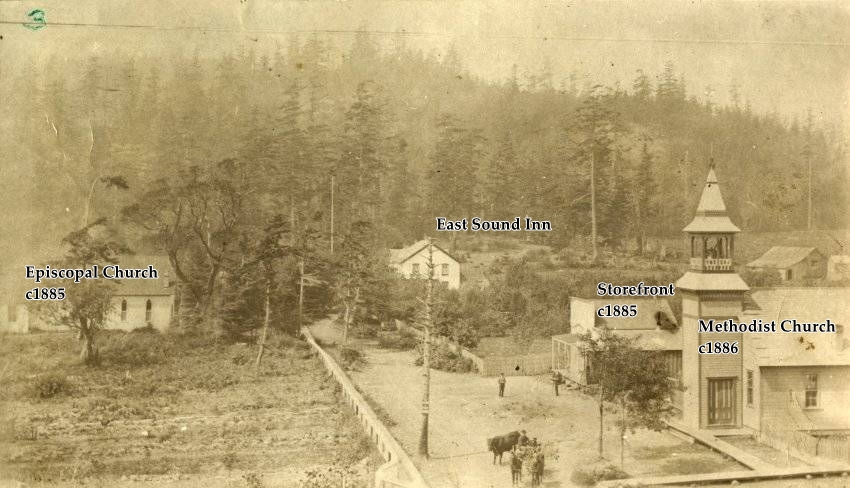

Eastsound

Eastsound – Čəlxwε’sή

Protecting the cultural sensitivity in the age of rapid development.

This project started out as a simple review of previous archaeological work in the area of this known Native American Village.

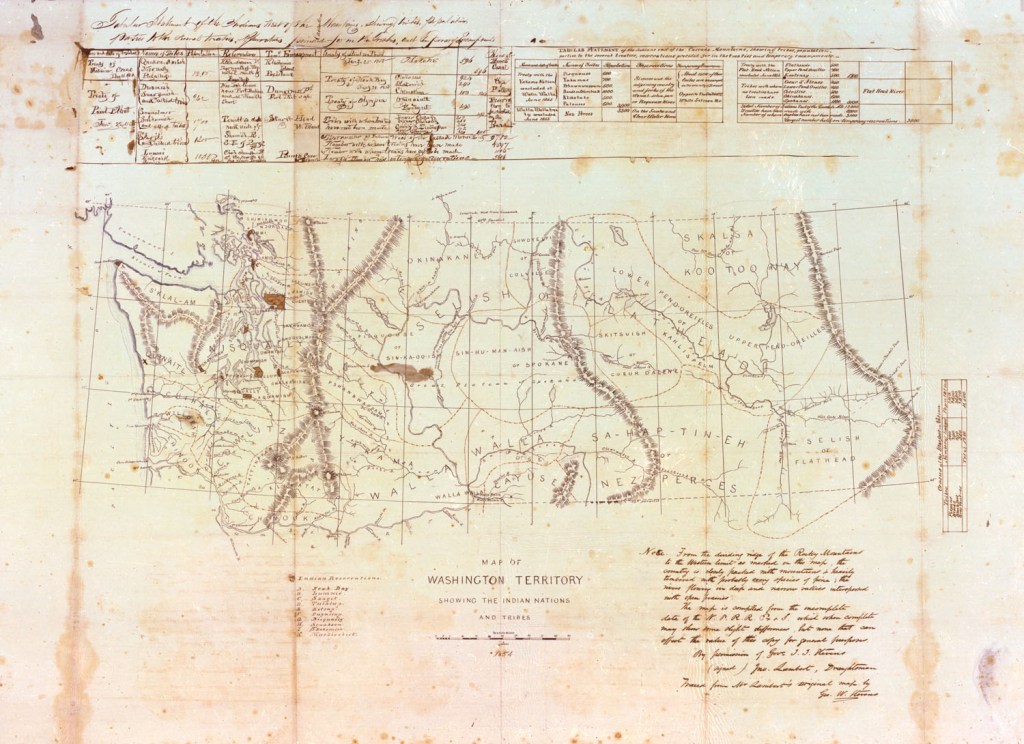

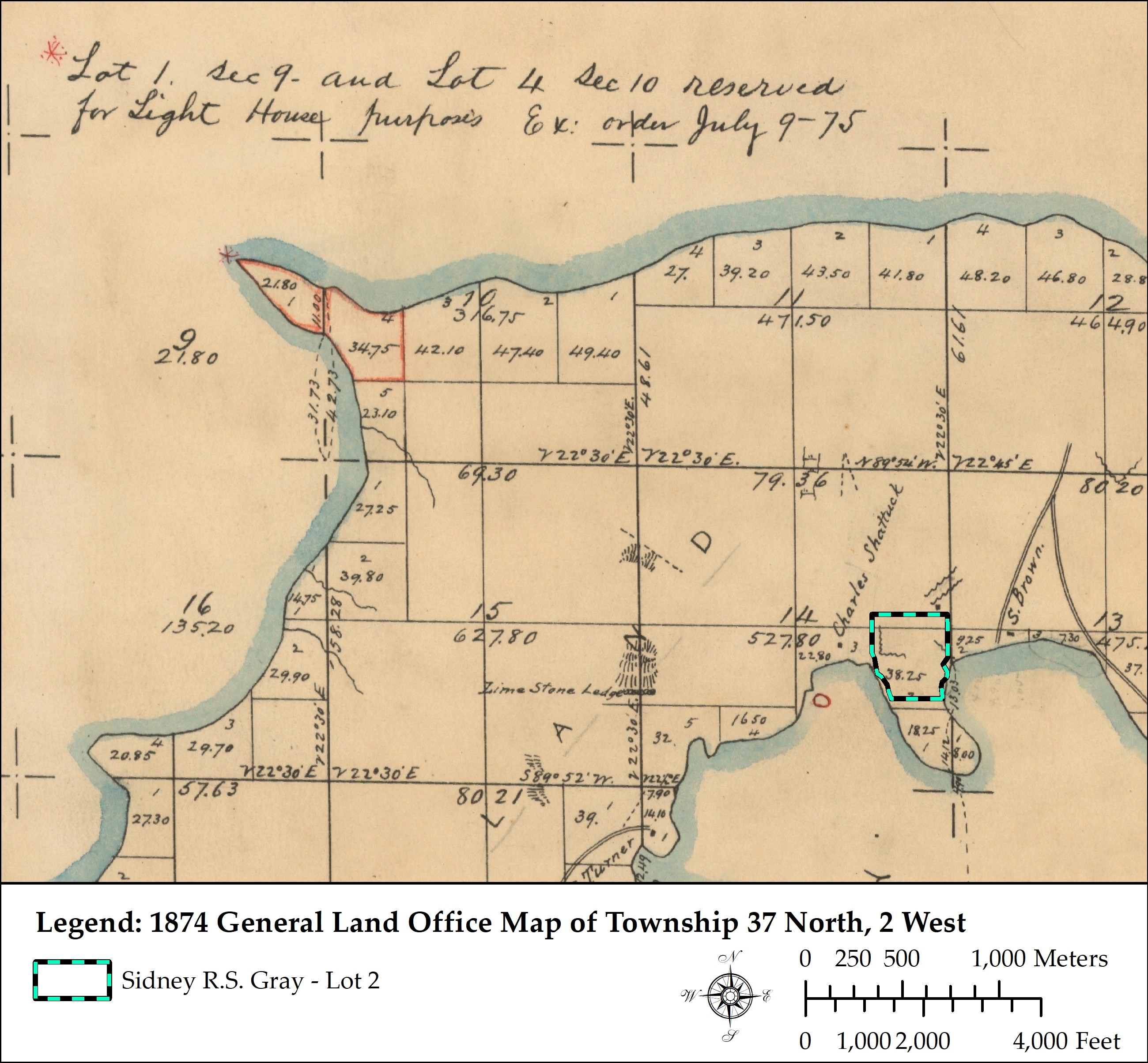

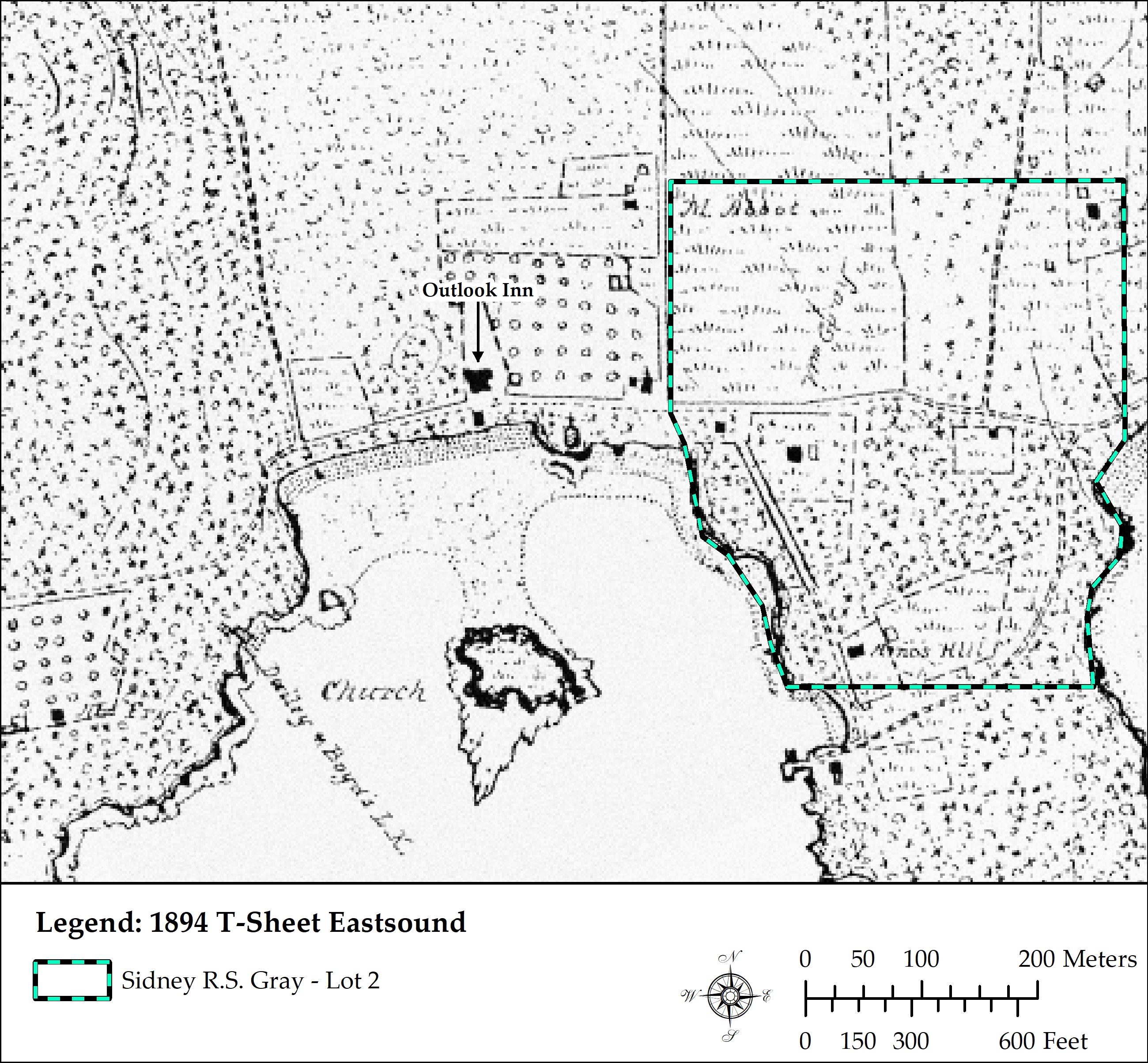

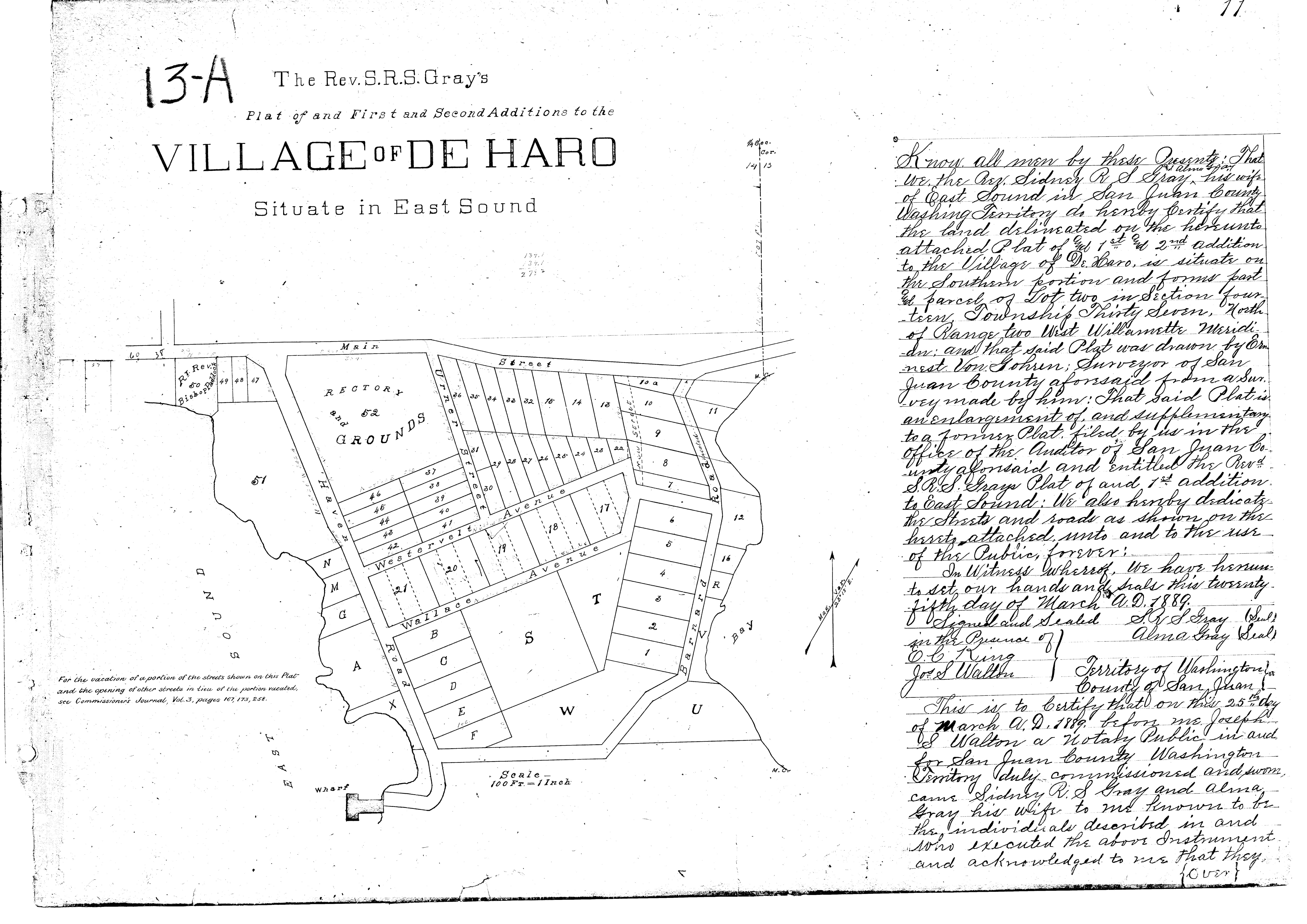

After an exhaustive review, it was clear that the vast amount of grey and historical material such as photographs, memoirs, maps, genealogical materials, land records, past cultural resource studies, and most importantly the local informant information was not being applied to the identification and preservation of this known native village.

Abbott Cultural Heritage created a digital media presentation for the Lummi Nation and with CRC Archaeologist, Genavie Thomas prepared a detailed report for the landowner, San Juan County, and the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP) for Washington State SEPA review. A few of the historic digital materials gathered and created for this project are displayed, due to confidentiality of sensitive information such as:

Archaeological locations can not be displayed publicly.

Ethnographer Wayne Suttles reported in 1951 that the name Swε′’lax was given to Mount Constitution and that the people who occupied three ethnographically-reported winter villages within the Eastsound inlet were known as the Swε′’lax people, a subdivision of the Lummi who lived on Orcas Island.

Frazier 2019

Underwood, Skamania County, Washington

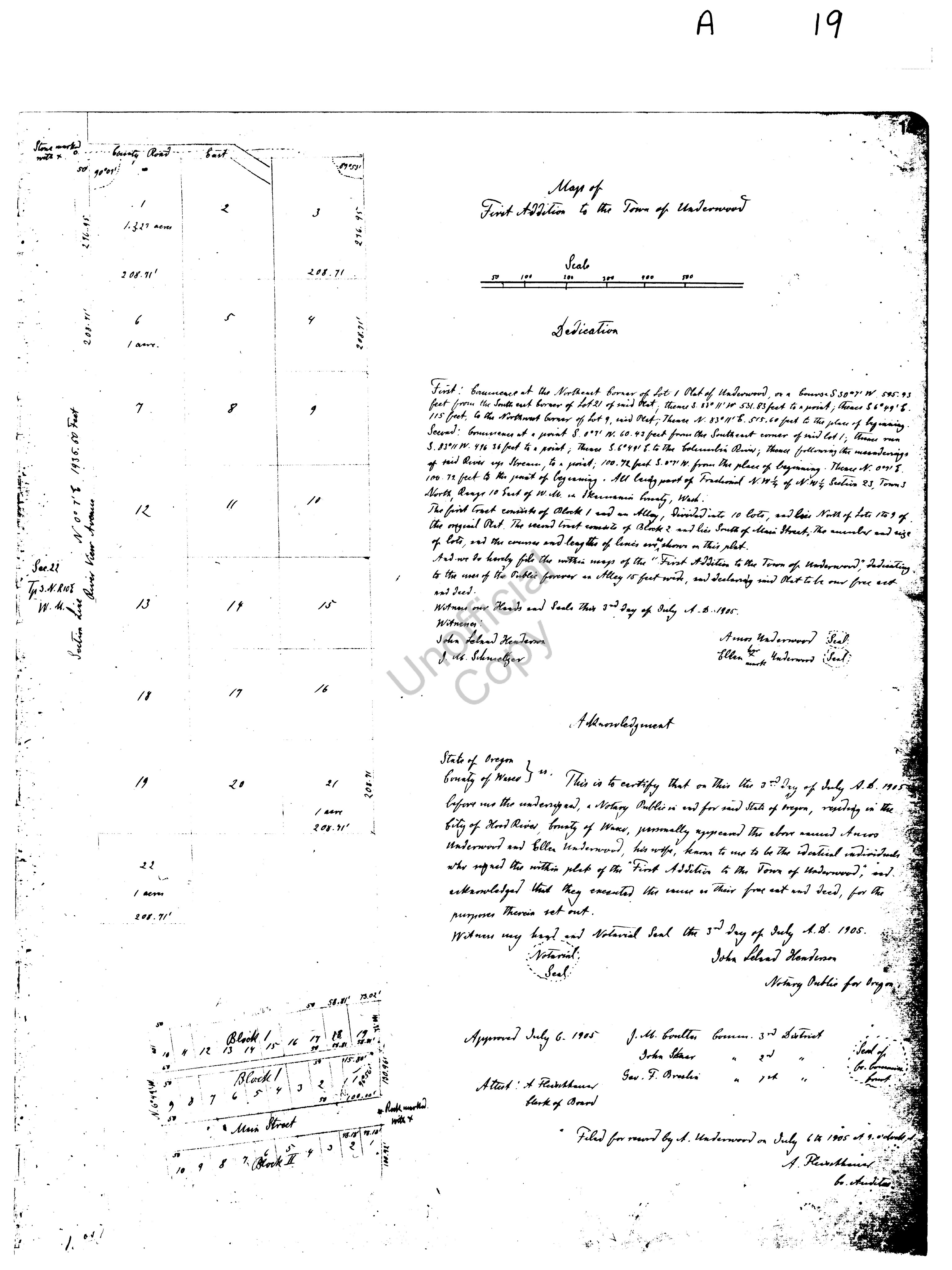

Underwood today is small community in Southwest Washington in Skamania County named for an early American pioneer, Amos Underwood. This community falls within the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area (CRGNSA) and much of the private and state land falls within the General Management Area (GMA) of the CRGNSA. Therefore projects are subject to both local county and federal permit conditions for the identification and protection of cultural resources per Chapter 22.22- General Management Areas of the Management Plan for the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. Abbott Cultural Heritage specializes in southwest Washington history and has had several cultural resource projects in this community which has provided this micro history into early inter-racial relationships.

History of Underwood

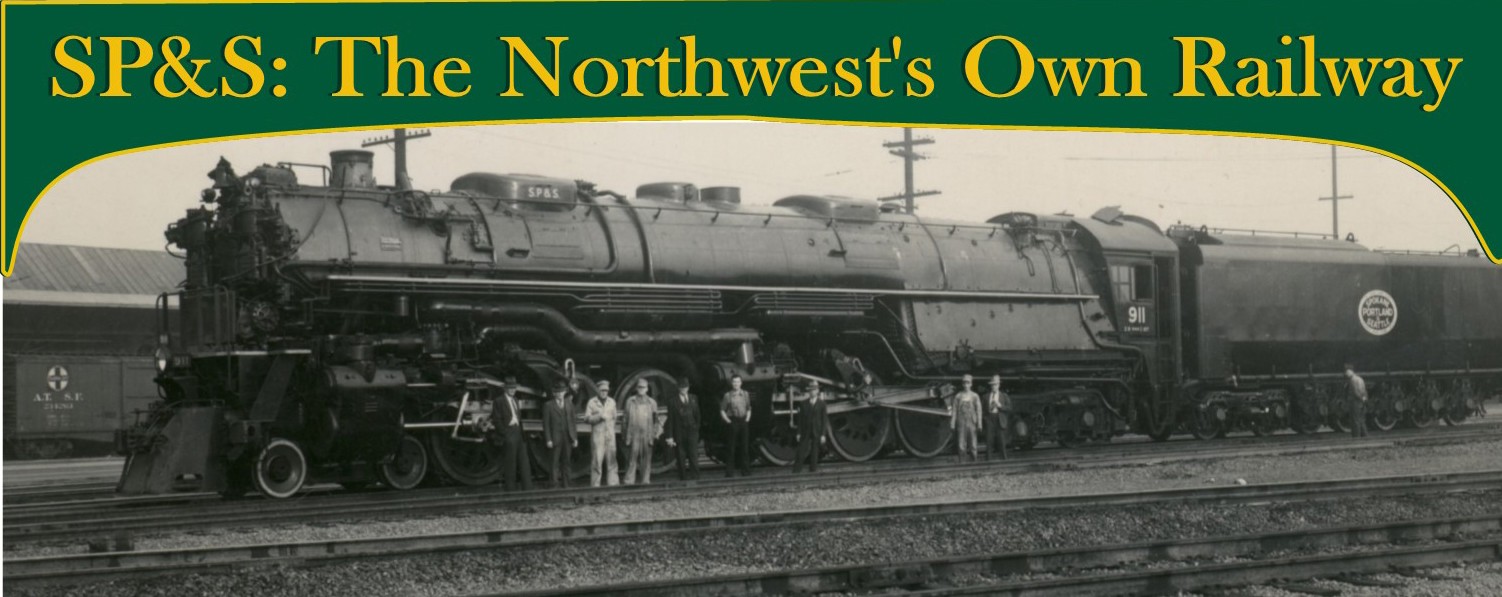

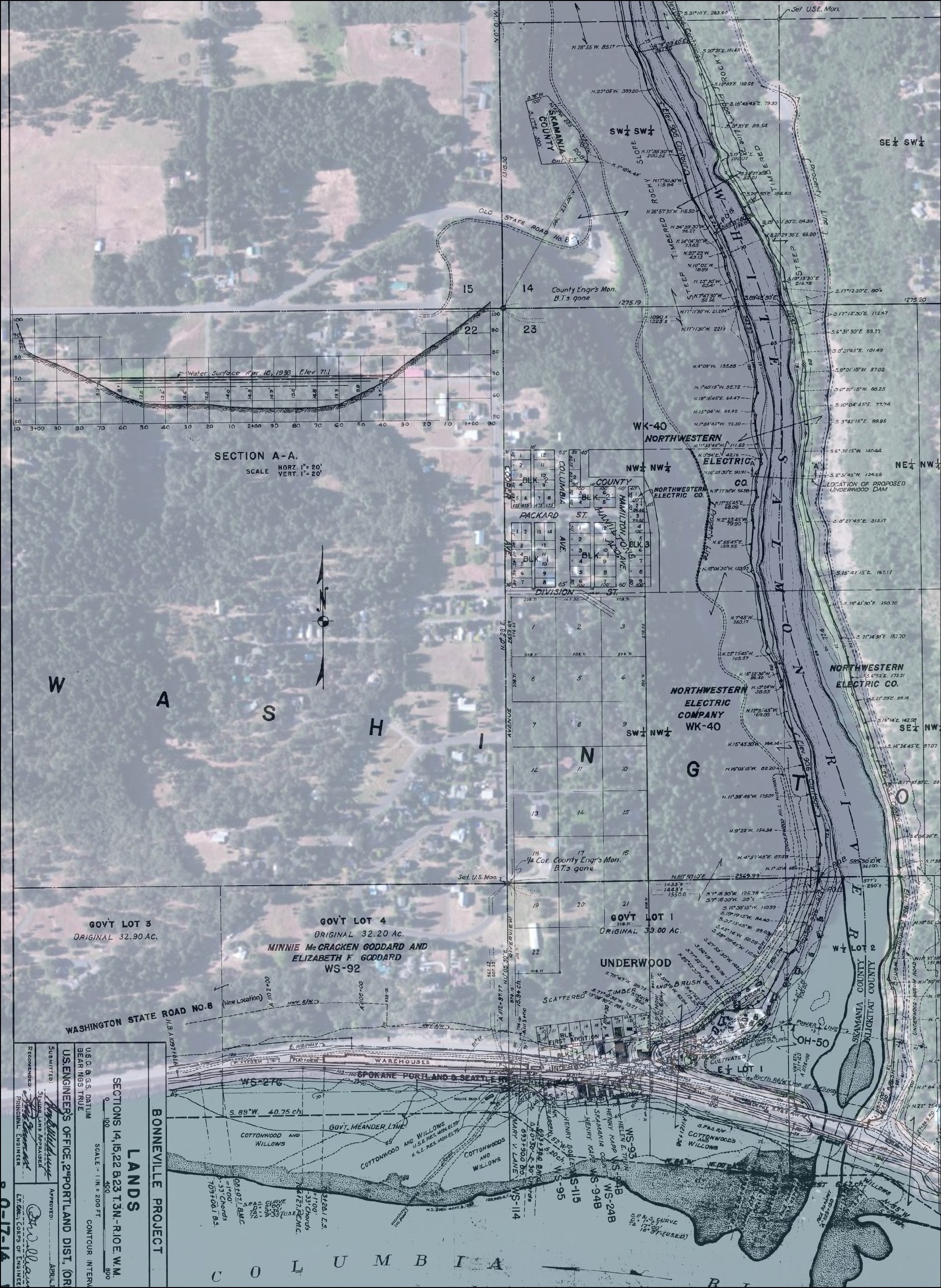

The Underwood community’s economy was historically based on the extensive timberlands, and after the land was cleared, the orchard industry took hold. Before 1908 there was very limited transportation opportunities to this region of the Columbia River Gorge and travel consisted of taking a series of steamboats and portage railways around the rapids that had been in use on both the Oregon and Washington sides of the Columbia River since the 1850s. Regular access to the north side of the Columbia River came with the development of The Spokane, Portland, and Seattle Railway (SP&S) at the turn of the 20th Century, this transportation improved the local agricultural industry. Construction on the North Bank Railroad, as it was initially termed, began in 1906 and officially opened March 11th, 1908. About the same time c1907 construction of the North Bank Highway also termed State Road No 8 began with later sections completed by 1916. This road follows present day Cook-Underwood Road north of the river up on the terrace, it was rerouted closer to the river over different time spans beginning in the 1930s with the planning for the Bonneville hydroelectric dam. The dam was planned to produce 500,000 kwh of power which in turn attracted aluminum processing plants to the Southwest Washington region during World War II and ultimately led to increased industrial development within the river’s settlements. The backwater from the installation of dam in 1934, caused the river to rise some 64 feet behind the structure. Shown is the original 1936 USACOE Survey Map overlaid onto a modern aerial used for HGIS analysis (Frazier 2020).

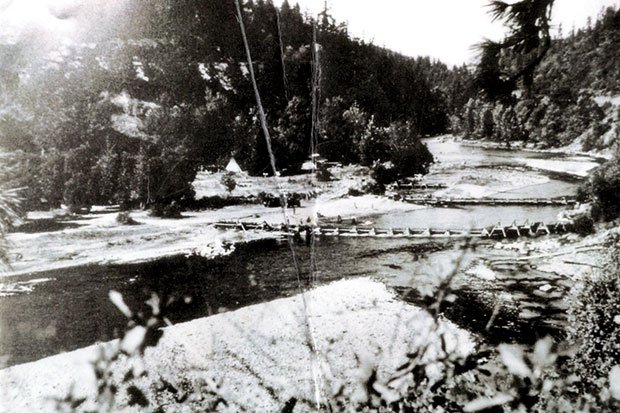

Andoniram (Amos) Judson Underwood was an early pioneer who came west on the Oregon Trail in 1852, along with his younger brother Edward Underwood. Amos Underwood moved to Cascade Locks and then to present-day Hood River, Oregon before claiming land on the north side of the Columbia River in Skamania County. The two Underwood brothers began purchasing and clearing land up on the fertile bluffs above the river where the town of Underwood would take hold. The brothers also owned land at the confluence of the Columbia and White Salmon rivers at the location of Namnit, a significant Native American Village reported by Edward Curtis in 1911 and shown in photographs gathered for this project.

In 1871, Amos remarried Ellen (daughter of Cascades Tribe- Chief Chenewuth) and Edward married Ellen’s 16-year-old daughter from her first marriage Isabelle Lear, in a double ceremony that was officiated by Reverend Joseph Condon. Ellen and Amos had been previously married in a Native American ceremony, so they decided to get married by a minister at the same time as their daughter.

Edward and Isabelle had 11 children: Lovica Jennie (1872-1943); Grace (1875-1949); Margaret (1878-1961); Cornellia Nellie (1880-1971); William (1882-1948); Lafayette (1886-1904-invalid at birth); Elsie (1888-1905); Sharlotte Lottie (1890-1915); Catherine Kate (1893-1940); James Corbett (1896-1951); and Isabelle (1905-1979).

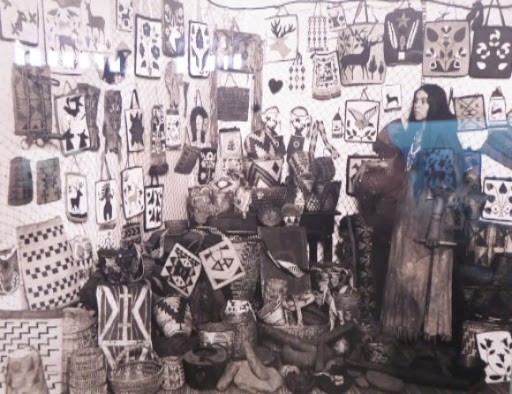

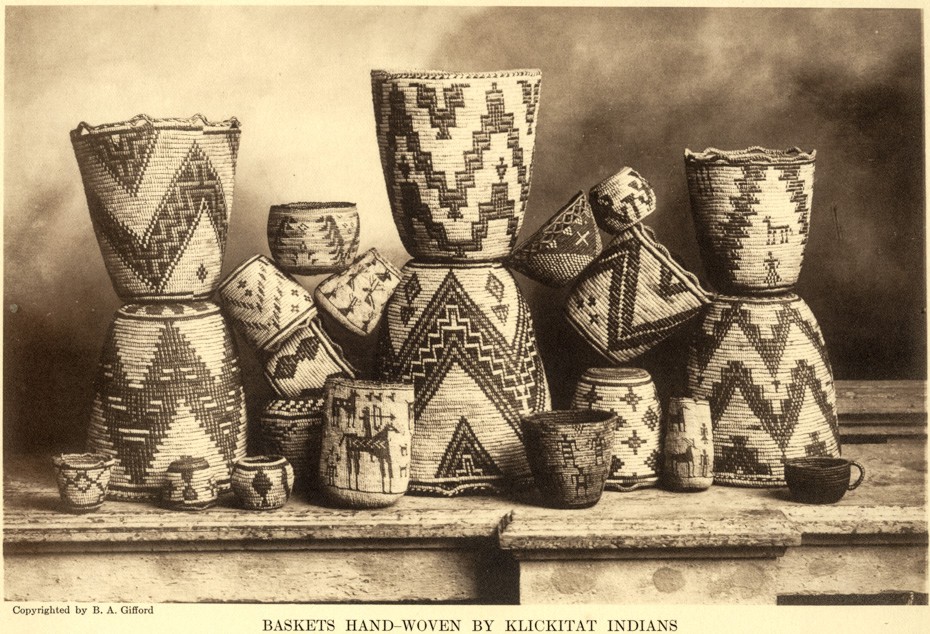

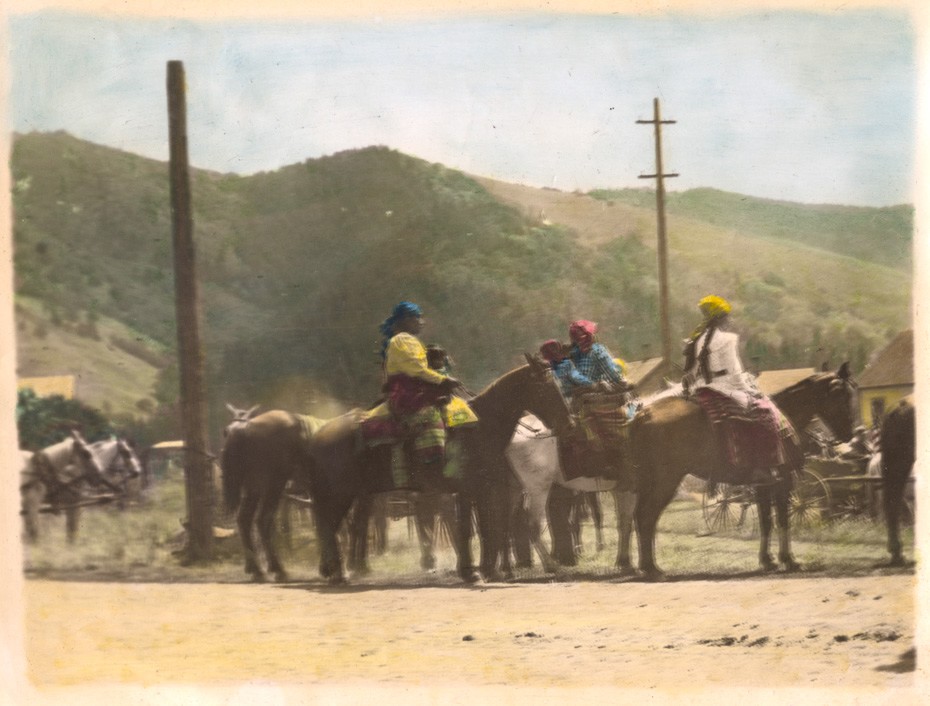

The two brothers were very proud of their wives’ artistic talents, especially their beautiful woven baskets and clothes decorated with intricate beadwork. In the late 1800s, the Underwood’s held an “Indian Fair” for neighbors and friends attracting people from the surrounding areas including Hood River and Cascade Locks, Oregon. The fair took place at the Underwood log house where Amos and Ed made racks to display Isabelle and Ellen’s finest work including baskets, beaded purses, dresses, necklaces, and other jewelry were all displayed. Fine basketry and beadwork made by Ellen’s mother, Martha, were also part of the display. The exhibit was accompanied by a picnic lunch prepared by the Underwood women. The Indian Fair became a tradition held every year into the early 1900s. Several photos of the fair, and Ellen’s craft are shown.

Edward planted orchards around his farm on previously cleared land and he helped his brother operate the Underwood Saloon and with his other business ventures, such as the Underwood Mining Company. Isabelle cared for her family and home while continuing her beading and basketry work throughout her life. She also practiced her faith as part of the Shaker Church, often using bells and candles in ceremonies before and after prayers at meals and bedtime. Edward and Isabelle’s farm became a gathering and trading place for many Native Americans in the area, especially in the fall during the salmon fishing season. Edward and Isabelle’s Farm is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Edward Underwood died February 15th, 1908 at the age of 62 leaving Isabelle a widow and nine surviving children. Despite the death of her husband, Isabelle continued her active role in the community. She moved to a small house near the Underwood Hotel to be with her daughter Mary who operated the hotel. In 1936, she was invited as a special guest to witness the reburial of Native Americans remains displaced when Bonneville Dam was being constructed. Because she was the granddaughter of Chief Welawa (Chenoweth), Isabelle was asked to unveil a monument granite monument inscribed with “Ankutty Tillikum Musem—Here Sleep the Ancient People” dedicated to the native people of the area and those reinterred due to the building of the Dam, The ceremony took place May 27th, 1936 at the Greenwood Cemetery in North Bonneville . Isabelle Underwood died later that year, 20 November 1936. Her obituary in the 27 November 1936, White Salmon Enterprise newspaper states:

Her memory will survive like the green grass above her grave not as that of the pioneer, but as a native born, daughter of aborigines, who were here centuries before the white man came with his covered wagons, railroads, automobiles and airplanes. We take off our hats and stand aside as she passes on to the great realm of the Great Spirit from which no traveler ever returns.

In 1946, the Underwood Hotel, operated by Amos and Ellen’s daughter Martha, and the heart of the platted town was destroyed by a catastrophic fire caused by a chimney spark; only a cabin, warehouse, and barn survived the fire. The town was never rebuilt and now a scant community is all that remains.

Interactive Map of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, provided by the Columbia Gorge Commission.